History of the Island

Prehistoric Crete

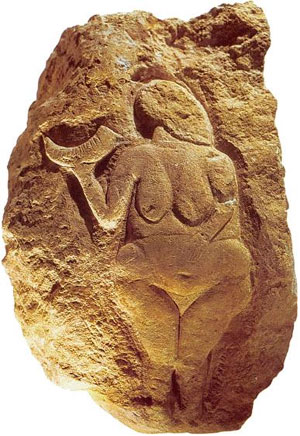

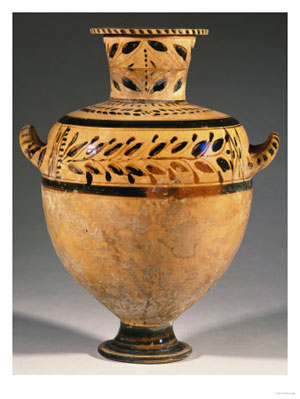

Some of the early influences upon the development of Cretan culture arise from the Cyclades and from Egypt; cultural records are written in the undeciphered script known as “Linear A”. The archaeological record of Crete includes superb palaces, houses, roads, paintings and sculptures. Early Neolithic settlements in Crete include Knossos and Trapeza.

Cretan history is surrounded by myths (such as those of the king Minos; Theseus and the Minotaur; and Daedalus and Icarus) that have been passed to us via Greek historian/poets (such as Homer).

Because of a lack of written records, estimates of Cretan chronology are based on well-established Aegean and Ancient Near Eastern pottery styles, so that Cretan timelines have been made by seeking Cretan artifacts traded with other civilizations (such as the Egyptians) – a well established occurrence. For the earlier times, radiocarbon dating of organic remains and charcoal offers independent dates. Based on this, it is thought that Crete was inhabited from the 7th millennium BC onwards. The fall of Knossos took place circa 15th century BC. Subsequently Crete was controlled by the Mycenaeans from mainland Greece.

Minoan-Mycenaean Crete

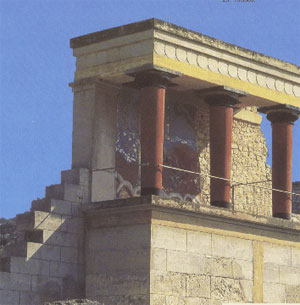

Crete was the centre of Europe’s most ancient civilization, the Minoan. Tablets inscribed in Linear A have been found in numerous sites in Crete, and a few in the Aegean islands. The Minoans established themselves in many islands besides Ancient Crete: secure identifications of Minoan off-island sites include Kea, Kythera, Milos, Rhodes, and above all, Thera (Santorini).History07

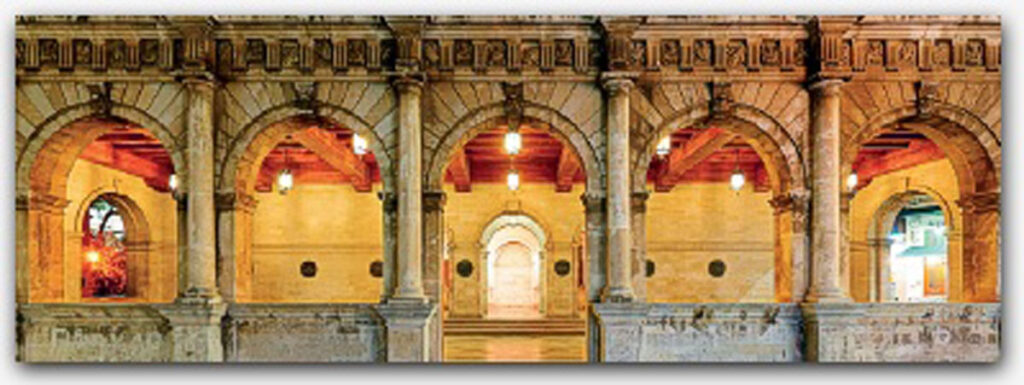

Archaeologists ever since Sir Arthur Evans have identified and uncovered the palace-complex at Knossos, the most famous Minoan site. Other palace sites in Crete such as Phaistos have uncovered magnificent stone-built, multi-story palaces containing drainage systems,[1] and the queen had a bath and a flushing toilet. The expertise displayed in the hydraulic engineering was of a very high level. There were no defensive walls to the complexes. By the 16th century BC pottery and other remains on the Greek mainland show that the Minoans had far-reaching contacts on the mainland. In the 16th century a major earthquake caused destruction on Crete and on Thera that was swiftly repaired.

Classical, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Arab Crete

History11In the Classical and Hellenistic period Crete fell into a pattern of combative city-states, harboring pirates. Gortyn, Kydonia (Chania) and Lyttos challenged the primacy of ancient Knossos, preyed upon one another, invited into their feuds mainland powers like Macedon and its rivals Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt, a situation that all but invited Roman interference. Ierapytna (Ierapetra) gained supremacy on eastern Crete.

In 88 BC Mithridates VI of Pontus on the Black Sea, went to war to halt the advance of Roman hegemony in the Aegean. On the pretext that Knossos was backing Mithradates, Marcus Antonius Creticus attacked Crete in 71 BC and was repelled. Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus with three legions to the island. After a ferocious three-year campaign Crete was conquered for Rome in 69 BC, earning this Metellus the agnomen “Creticus.” At the archaeological sites, there seems to be little evidence of widespread damage associated with the transfer to Roman power: a single palatial house complex seems to have been razed. Gortyn seems to have been pro-Roman and was rewarded by being made the capital of a province that at times joined Cyrenaica to Crete.

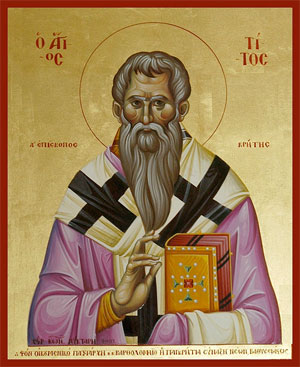

Gortyn was the site of the largest Christian basilica on Crete, the Basilica of Ayios Titos dedicated to Saint Titus, the first Christian bishop in Crete, to whom Paul addressed one of his epistles. The church was begun in the 5th century. As revealed in the Epistle to Titus in the New Testament and confirmed by Cretan poet Epimenides the people of Crete were considered by these Christians to be liars and gluttons. (Note: Epimenides was a 6th century poet. Paul cited him in Titus, but he cannot be said to confirm anything)

Crete continued to be part of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine empire, a quiet cultural backwater, until it fell into the hands of Iberian Muslims under Abu Hafs in the 820s, who established a piratical emirate on the island. The archbishop of Gortyn (Cyril) was assassinated and the city so thoroughly devastated it was never reoccupied. Candia (Chandax, modern Heraklion), a city built by the Iberian Muslims, was made capital of the island instead.

Venetian and Ottoman Crete

In the partition of the Byzantine empire after the capture of Constantinople by the armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Crete was eventually acquired by Venice, which held it for more than four centuries (the “Kingdom of Candia”).

The most important of the many rebellions that broke out during that period was the one known as the revolt of St. Titus. It occurred in 1363, when indigenous Cretans and Venetian settlers exasperated by the hard tax policy exercised by Venice, overthrew official Venetian authorities and declared an independent Cretan Republic. The revolt took Venice five years to quell.

Modern Crete

After Greece achieved its independence, Crete became an object of contention as the Christian part of its population revolted several times against Ottoman rule. Revolts in 1841 and 1858 secured some privileges, such as the right to bear arms,History08 equality of Christian and Muslim worship, and the establishment of Christian councils of elders with jurisdiction over education and customary law. Despite these concessions, the Christian Cretans maintained their ultimate aim of union with Greece, and tensions between the Christian and Muslim communities ran high. Thus, in 1866 the great Cretan Revolt began.

Cretan State

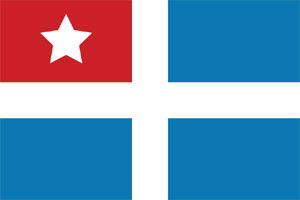

A new Cretan insurrection in 1897 led to the Ottoman Empire declaring war on Greece. However, the Great Powers (Britain, France, Italy and Russia) decided that Turkey could no longer maintain control and intervened. By March 1897, the Great Powers decided to restore order by governing the island temporarily through a committee of four admirals who remained in charge until the arrival of Prince George of Greece as first governor-general of an autonomous Crete, effectively detached from the Ottoman Empire, on 9 December 1898. Turkish forces were expelled in 1898, and the independent Cretan State (Official Greek name: Κρητική Πολιτεία), headed by Prince George of Greece, was founded.

Prince George was replaced by Alexandros Zaimis in 1906, and in 1908, taking advantage of domestic turmoil in Turkey as well as the timing of Zaimis’s vacation away from the island, the Cretan deputies declared union with Greece. But this act was not recognized internationally until 1913 after the Balkan Wars. By the Treaty of London, Sultan Mehmed V relinquished his formal rights to the island. In December, the Greek flag was raised at the Firkas fortress in Chania, with Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine in attendance, and Crete was unified with mainland Greece. The Muslim minority of Crete initially remained in the island but was later relocated to Turkey under the general population exchange agreed in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece.

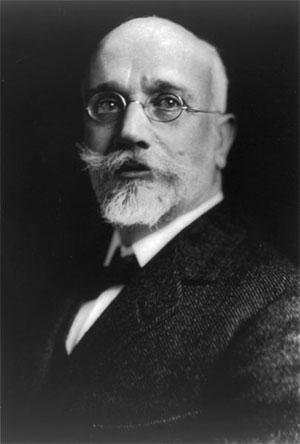

One of the most important figures to emerge from the end of Ottoman Crete was the liberal politicianHistory02 Eleftherios Venizelos, probably the most important statesman of modern Greece. Venizelos was an Athens-trained lawyer who was active in liberal circles in Hania, then the Cretan capital. After autonomy, he was first a minister in the government of Prince George and then his most formidable opponent. In 1910 Venizelos transferred his career to Athens, quickly became the dominant figure on the political scene and in 1912, after careful preparations for a military alliance against the Ottoman Empire with Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria, allowed Cretan deputies to take their place in the Greek Parliament.

In late May 1941, Crete was the theater of the first major airborne assault in history. After a fierce and bloody conflict between Nazi Germany and the Allies that lasted ten days, the island fell to the Germans. However, despite their victory, the elite German paratroopers suffered such heavy loses that Adolf Hitler forbade further airborne operations of such large scale for the rest of the war. From the first days of the invasion, the local population organized a resistance movement, participating widely in guerrilla groups and intelligence networks.

In reprisal, the Germans ordered numerous brutal attacks against Cretan civilians. Standing out among the list of atrocities, are the holocausts of Kedros (Amari) and Viannos, the destruction of Anogia and Kandanos and the massacre of Kondomari.